Pasta Machine Product Management

Leading with constraints

“You’re not allowed to create mockups.”

“What do you mean?”

“The product designer on your team is getting annoyed at you.”

I was flabbergasted. How dare they treat the product manager this way. Was I not the CEO of the product? If I don't create mockups, what do I do?

After many years as a control-obsessed founder where my team acquiesced to my whims, it was a rude awakening when I joined another startup and a team of highly competent peers. I needed to learn the core essence my role as a Product Manager.

Although product management is the inspiration for this article, the general principle of leading with constraints has pretty broad applications.

Product Managers define things

The role of a Product Manager (PM) is to ensure that the right products get built.

Whether it be a new model of washing machine or a new app, product managers are responsible for working with Product designers and Engineers (and others) to bring new products into the world and to improve them.

“Right” is deliberately ambiguous. It’s up to you to make a case for what that means in any given situation. And it’s up to them to usher that product into the world.

“Right” doesn’t mean “whatever you sketch on a napkin”. That’s just asking for mini-tyrants on power trips ignoring reality and demanding that all their brilliant features get built.

You need to build a case for what the right product is. But how do you build a case for a solution that you’re not allowed to design?

Leading without prescribing

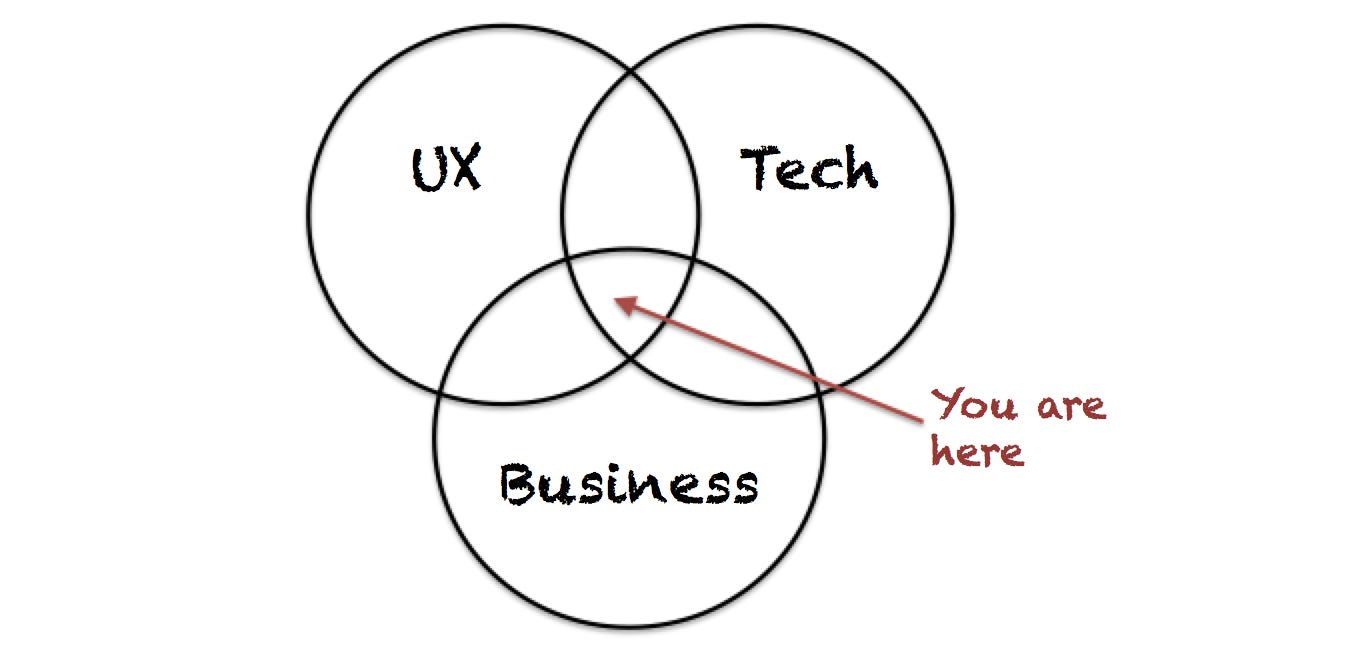

You’ve probably seen this diagram below showing product sitting at the intersection of various domains.

If the product is a bad user experience, then clearly it’s not the “right” product.

If it doesn’t achieve the appropriate business goals (causes the company to go bankrupt) or if it’s not feasible to build (takes 5 years), then clearly it’s not “right” either.

In other words, these are three areas where you have constraints on what the right product could be.

But these constraints still don’t go far enough. You’re not very useful if all you repeat all day is “it must be a good user experience”.

You need constraints that are specific enough to affect decisions on the solution itself.

Let’s go through some examples.

Product management 101: Problems are constraints

One of the fundamental questions a PM needs to champion is “what problem is this trying to solve”. If a product doesn’t solve a problem, why is it needed?

As an example, a PM working at an online marketplace for pet owners to find dog walkers could propose a new feature to track the dog walker via GPS.

Clear enough, right?

Here’s one interpretation:

Problem: I’m anxious about where my dog is .

You probably need real time tracking and an easy way to contact the dog walker if they’re going off course.

And here’s another interpretation

Problem: I don’t know if my dog walker actually walked my dog.

Maybe you don’t need real time tracking, and a daily summary is enough.

A mockup is a terrible constraint because nobody knows whether you definitely want that ugly button in the corner, or whether it’s an arbitrary placeholder.

A problem statement on the other hand, is a useful constraint because it tells you what’s actually important and what the product must be able to solve. And you can hold your team to account for whether the solution is actually likely to solve the problem.

User behaviour can create constraints

Your product has to work in accordance with how users actually behave.

If you know your users usually have more than 1 dog, that’s a pretty important behaviour to cater for. You might need to show multiple dogs on the map or support adding the profiles of multiple dogs. Therefore, “must support multiple dogs” could be a constraint.

Other constraints due to user behaviours could be things like:

Must be able to check location on the go

Must support walks of up to 3 hours

Must support pet sitters walking dogs from multiple owners at the same time

Constraints need to be justified

Because constraints change the entire direction of a product’s design, a large part of your job is making sure your constraints are actually true.

Your level of confidence in a constraint should be proportional to the impact that it will have.

Let’s take the example of a company that makes fans.

“Customers don’t want to get out of bed after they’ve gotten in bed” is probably a safe enough assumption that you don’t have to test.

“Customers can’t fall asleep because their fan is too loud” might be the central basis of your new product, and you probably want a lot of evidence before building the full product.

Do you have a shared understanding of what is true?

When it comes to design, everybody has an opinion.

The most useless conversations are when Person A says “I think it should be X” and Person B says “I think it should be Y” and they decide to duel to the death.

Usually, it just means that you didn’t build a shared understanding of constraints that you were building for. You might be misaligned on the goal or the scope.

More commonly, the different parties might just have different assumptions on how users behave because you didn’t make those behavioural constraints explicit.

For example, if you’ve got good data showing that most of your target customers don’t want the fan to stay on all night, nobody should be arguing about the necessity of a feature that automatically turns it off.

Internal constraints

Of course, many constraints are internal not external.

Technical - What’s feasible technically?

Getting the noise down to 50 decibels will take 3 months, while getting the noise down to 25 decibels will take 12 months.

Business - What business goals does the product need to serve?

We want 1,000,000 new customers in the next 3 years

Stakeholders - What do your stakeholders want?

The leadership team feels like we’re not innovating enough. We need something transformative, not something safe.

Turns out, if you discuss constraints with your team, you have some pretty useful discussions.

And if you hold the team accountable for meeting these constraints, you can create some pretty cool solutions together.

Building the pasta machine

Leading with constraints is like using a pasta machine. You put in your raw ideas and roll it into something slightly more refined.

As your team discovers more accurate constraints, you have tighter boundaries within which you have to design. Your solution needs to become more elegant.

And so for your next iteration, you set the pasta machine to a tighter setting and put the dough through once more.

Good products take many iterations to get right.

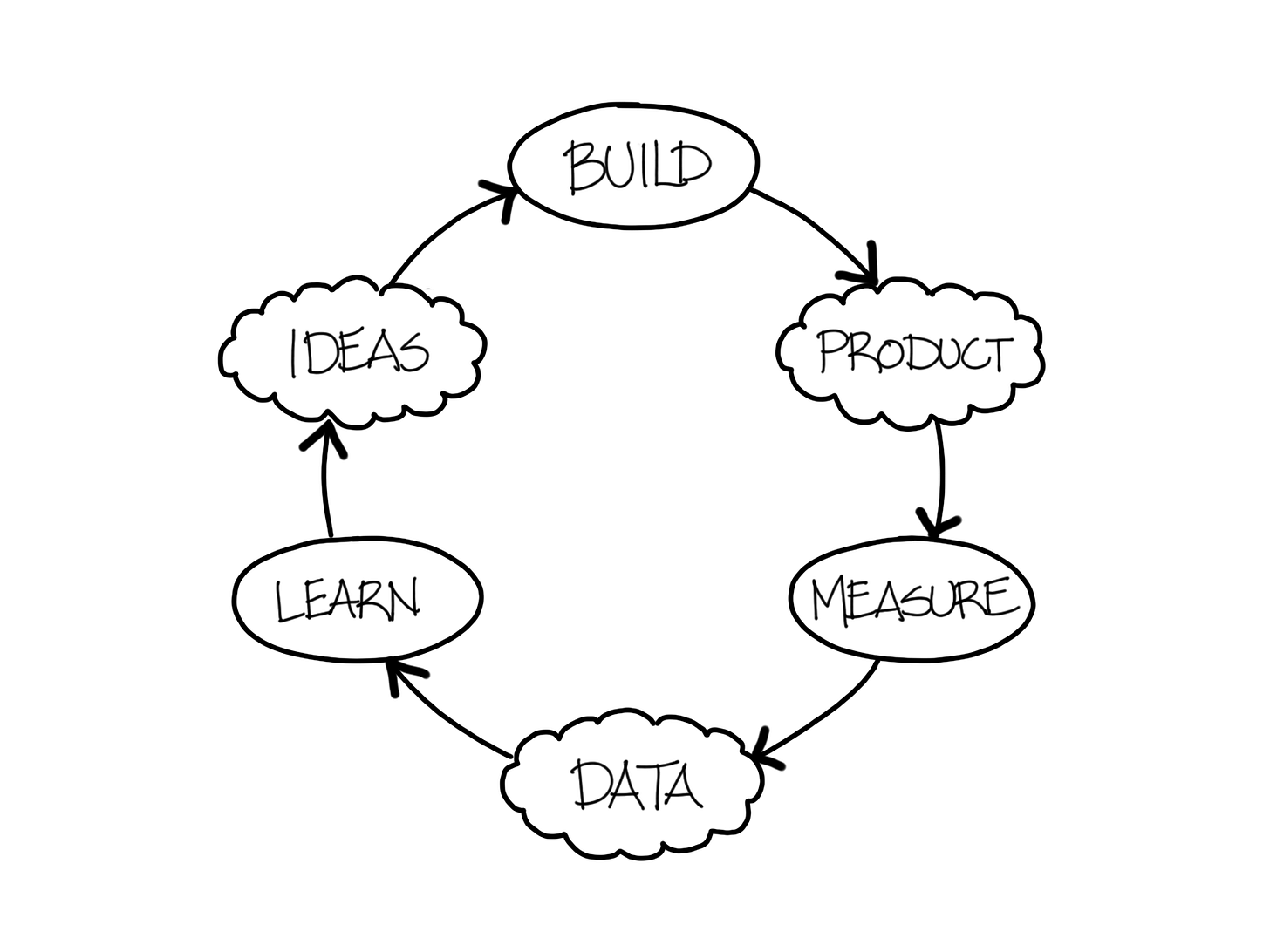

In the standard lean startup framework, you’re meant to build a product, measure the results, get the data, and learn.

“Learn” just means acquiring a more accurate set of constraints to tighten your pasta machine with. Some of your original constraints might change, or you may discover new ones.

Of course, it’s just a metaphorical pasta machine

Most companies have a document somewhere that serves as the source of truth for a new product, often called a Product Requirements Doc (PRD).

PRDs are often described as living documents. In practice, after the project has begun, it’s common for them to be treated as something set in stone. Alternatively, they can be forgotten entirely.

This document is your pasta machine. It contains all the constraints and decisions that dictate what product gets built. Use it. Update it.

The purpose of a PRD is not to build a case for your favourite solution. The purpose is to articulate the latest understanding of constraints and the best solution that has emerged so far.

It means that as you’re iterating on constraints and the solution, the document becomes more objectively accurate.

Okay, maybe mockups are fine

I’m not advocating for non-designers to be banned from creating mockups.

We all love sketching ideas and solving problems - it’s in our nature.

I’m saying that non-designers shouldn’t confuse sketching mockups with where they add the most value.

Go crazy, make your mockups.

But then sit down and try to articulate what constraints you are trying to express with that mockup. What problem is it trying to solve? What have you assumed about the user? What must be achieved technically? What business goal does this serve?

Then get up and do the hard work of talking to your customers and your stakeholders and figuring out whether those constraints are actually true.

The right product is the one that most elegantly fits the most appropriate constraints.

If you lead through constraints rather than prescribe solutions, you will help your team take ownership for their areas, and you will create better products.

Build a beautiful pasta machine together. And the pasta will turn out beautiful.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed that, subscribe below to receive new posts.

If you have any thoughts or feedback, please let me know.